An immigrant who would rather go home than get rich, photographs of New York life in the late 1920s, a story of courage and opportunity: That’s three of the many things Uli Balß discovered in a box he inherited. Against all odds, the head of German record label JARO Medien turned those letters and photos into a book. Here’s his story.

This is the English version of my interview with Uli Balß – hier geht’s zur deutschen Fassung.

Family history is oral history, which means the clock is ticking: One day your ancestors won’t be able to tell it like it was. Except when your grandfather happened to be a bookbinder, I want to say now, inspired by reading a book called “New York: Past & Present“.

born in Herford, Germany,

went to NYC for the first time about 30 years ago,

owns a music publishing company in Bremen, Germany,

includes a cd in his book “New York: Past & Present”,

and loves biking so much that he doesn’t blink at the fact that his grandpa used to ride his bike from Leipzig all the way to eastern Westfalia (more than 200 miles) when he came to visit.

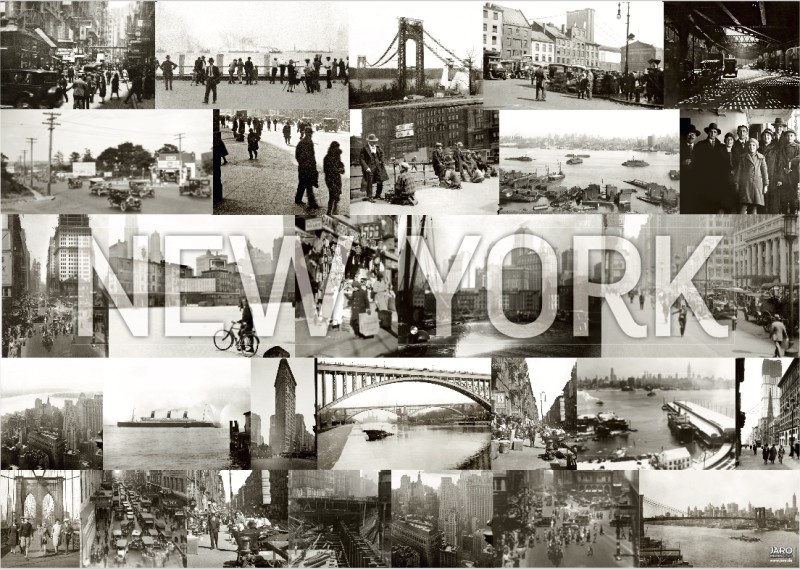

As a bookbinder, Theodor Trampler neatly bound the letters he had written to his family in Leipzig while living in New York in 1928 and 1929. They answer many questions you may have about what the life of a German in New York at the time might have looked like – and even what New York itself looked like back then. Cause it turns out Theodor Trampler was an avid photographer, he even turned his passion into a side job, selling photos to newspapers and magazines on both sides of the Atlantic. All this would still be forgotten, collecting dust on microfiche somewhere, if Trampler’s grandson wasn’t such a pighead.

Uli Balß has a lot on his plate, so going to New York to research his family’s history wasn’t on top of his list. It wasn’t on his list at all. Though he happily admits his fascination for the city, New York is a place where he goes for business, period. In the early 1980s, Balß founded JARO Medien in Bremen, Germany: Carrying a conglomerate of jazz and rock not only in his company’s name, he has worked with a world-spanning mix of music and a lot of passion in his heart – making the latter his business model, too.

When he discovered his grandfather’s collection of letters and photos in 2015, he didn’t think much of it. But soon enough, he felt: There’s more than family history in it. Soon enough, he was enthralled, and that’s something he knows from music: No matter how much other people dismiss your idea, there are things you just have to do because it’s the right thing to do. So let’s go! Oh, not so fast.

A squiggly problem is blocking Balß’s path to his grandfather’s New York experience: Sütterlin, a German handwriting script taught in schools until the 1940s, and very different from the Latin alphabet used today. In our interview, Uli Balß reveals how he learned to decifer his grandfather’s letters, how 1928 overtime hours are linked to current politics, and what, then and now, helps us feel less alone in this world.

Uli, your book about your grandfather Theodor Trampler’s letters is not telling a success story trailing the typical “from rags to riches” legend, but the story of an immigrant who left New York to go back to where he came from. How do people react to that?

Making the book took me about two and a half years, and of course I talked to people before it was finished. When they asked “what are you doing?”, I’d say I’m working on a book about my grandfather. In return, I often heard: “There was something similar in my family, too. My uncle also went to America, and he came back, too.” So you have this image in your head of people going to the U.S. and staying there forever, becoming citizens – but that’s not correct at all. I don’t know the numbers, I don’t know how many of these people came back, but there were at least a bunch of them.

In the 1800s, for instance, there were many Germans in the American prairie who didn’t stay because they wanted to, but because they couldn’t afford the return trip.

My grandfather also couldn’t afford the trip in the other direction. He had lost his job, and that was the driving force behind going to America. He needed work, he had a wife and two small children to support, and at the time, there was no such thing as unemployment insurance in Germany. Eventually, his friend, a man called Kurt Naegler, paid for the passage. They had been apprentices together in Leipzig.

That’s something I find quite remarkable: This friendship endured even though Kurt Naegler first went to England and then to New York. Do you know how they stayed in touch?

Back then, there was no internet, and I have no idea how that worked. Although Naegler had been trained as a bookbinder, he became a wirewalker, a tightrope artist, working in Manchester, UK, and elsewhere. I have no clue how he later found his friend in America; I didn’t get the impression that they exchanged letters on a weekly basis. But somehow, they had a connection and liked each other, otherwise they wouldn’t have kept in touch. And then Naegler said: “It doesn’t matter, I’ll send you the money and you pay it back later, then everything will be alright and you will have work here.”

Immigration is an issue today, too – in Germany as well as in the U.S. Do you think your book is related to today’s question of what immigration actually means?

It certainly is for me. It didn’t feel like a coincidence that the discussion about German far-right groups like Pegida and AfD started around the time I was working on the book. For me, the book is historical evidence: There was an opportunity for my grandfather to go to America. There was an openness, you were given the chance to do something different, and there were little constraints and barriers for that, relatively speaking. I think this is a good example of how to deal with one another. People should read this to see how important it is to be open towards other people and foreign cultures. The book proves how that works, at least that my grandfather didn’t have any problems in this regard.

The idea that people arrive in a foreign place expecting a bed of roses is nonsense – in your grandfather’s case, anyway. How do you feel about his work ethic, 90 years later?

He arrived in New York in the afternoon, and the next morning at six a.m., he was in the subway already, on his way to work. Reading this impressed me a lot. You would think: Well, you want to settle in first, so he’ll stay with his friend for a week or two, getting used to the city, and then take it from there. But the reason for all this was to make money, and to put the plan into practice as quickly as possible.

Your grandfather writes about his work a lot, from how cold the bookbinding workshop was to what his bosses were like, he criticizes the amount of overtime, and he talks about extra money from his side gig as a photographer. That reminds me of contemporary life in New York, where many people also do more than one job to make ends meet. Do you think this practice has made its way to Germany, or are ideas of how you work and when it’s time for “Feierabend” (yes, Germans have a word for after-work!) still different?

I think these ideas were very different at that time. Today, things are similar in Germany, people don’t stay in one profession for all their lives, they change jobs, and much more flexibility is required of them. There is a backlash against that, for instance prohibiting employees from checking work email during their vacation, so there is an effort to separate work from the rest of your life. And I like that, I think it is important for people not to be on call all day, every day. That is pretty hard for me, though, because I work in the music industry. When my artists are on tour and I am the one who organized that for them, of course they’ve got to have an emergency number to reach me in case there is any problem. But luckily, they hardly ever bother me.

Your grandfather would have very much liked fixed working hours, and he mentions the union. He writes that he would have liked to join, but that a union membership might prevent him from getting jobs. At the time, people would have probably called him a socialist.

Exactly, and that’s how he saw himself. I found a party membership book [in Germany, political parties require a membership with dues etc., which used to be documented in a passport-like booklet and nowadays mostly look like credit cards]: He was a member of the SPD, the Social Democratic Party. To think about that! If he had sensed what would happen a short time after his return with the Nazi takeover of 1933, as a socialist, he would have never returned, definitely. He would have told his wife: You have to come, we can’t hold out there.

How did he do as an SPD member after his return to Germany?

He abstained from speaking out politically, found a job at some point, and worked as a bookbinder until his retirement.

According to your grandfather’s letters, your grandmother seems to have contemplated following him to New York with the kids. Do you know why she didn’t do that?

Ultimately, she worried coming to a foreign country might harm the kids. That’s why she couldn’t make up her mind, and my grandfather told her: If you are 100 percent sure you want to come, then come. If not, I’ll come back.

The book makes it look like he’s dreaming of going back all along.

He clearly missed his wife and his children, and I believe that’s behind his homesickness. At the time, my mother was eight years old, my aunt was five years old. If he loved his children, which I assume he did, it must have been hard to leave them behind. Apart from that, the way I remember him, he would have done well in New York. But this bond was crucial for him. He also loved books and the opera, and he missed that in New York. [I clarified this part with Uli, because of course there were books and operas in New York, too – but hardly in German. The language was the problem!]

You learned about his time in New York through the letters and photographs you later published. How did you get a hold of them?

I inherited those documents after my mother had died in 2015. I found a drawer with bound albums, there were postcard albums – people used to collect postcards back then – and two photo albums plus three albums of letters my grandfather had written during his time in America and sent to his wife in Germany. Since he was a professional bookbinder, he had bound them and preserved them for the future.

Those letters are written in Sütterlin. How did you learn how to read them?

Learning Sütterlin was a challenge. At first, I asked elderly people for help. They had learned Sütterlin at school, and they said, sure, no problem, come visit and bring those letters. But once they laid eyes on them, they soon gave up. Everyone’s handwriting is different, and when my grandfather was exhausted after work, his handwriting became fuzzy, changing its size all the time, swinging like his moods. You really have to burrow into this writing style. To make things harder, I only found a single website where I could learn that. It features several old German scripts, among them an eight page letter in Sütterlin, outfitted with a mouse-over effect allowing you to see the Latin letters of each line. After I’d tried hard to memorize the alphabet in Sütterlin, which you will find all over the internet, I put an alphabet next to me and tried to learn the script with this internet page letter, line after line. After reading the letter many times, you commit to memory how the letters of that alphabet look in conjunction with others. That’s how I learned Sütterlin, bit by bit. When I finally started reading my grandfather’s letters, a single page first took me 20 or 30 minutes, it felt so foreign. At the end, I could read it almost fluently.

Can you write it, too?

No, I’ve never tried that. But if I didn’t have anything to do, I could start a side business and offer professional Sütterlin, well, translations, that really is almost like a translation. But I’m glad I did it, because after me … well, my two sons for sure wouldn’t do that. They never met my grandfather, after all, and they lack the personal motivation to sit down and learn to read the script. But now it is preserved, and of course it is also nice for my own, private family history.

Looking at the scope of your music company’s roster, I would say your grandpa’s homesickness is not your cup of tea. You rather seem to be in the business of spreading wanderlust, aren’t you?

Yes, maybe a little.

What makes music from Tuva, Georgia [the country, not the U.S. state], or Brooklyn so intriguing for you?

That’s very simple: I just think it sounds really good. There is no strategy behind that, like saying: It has to be this or that. I listen to something, and it either enthralls me or it doesn’t. It worked just this way with that Bulgarian women’s choir, for example. When I played their music to other people, they would say: “What on earth do you want to do with some Bulgarian housewives? No one’s going to be interested in that.” Nevertheless, I produced and published a cd, and within three months, Newsweek called from America, asking for an interview with me. That’s how I’ve always rolled, doing things I feel strongly about. Just like my next book project: That’s going to be about Tuva.

Does your work with music bring the world to you or do you travel yourself?

Luckily, my work allows me to travel. If you don’t let commercial considerations define your job, your threshold for frustration needs to be sky-high, and travelling sometimes serves as a compensation. It’s great to travel to Japan or India, to Australia, New Zealand, or somewhere in Europe. In times when money was tight, it was kind of a satisfaction for me to go on the kinds of journeys that others didn’t. But of course that only happens if you generally have a curious mind. I mean, I hitch-hiked to India as a student because I’ve always been interested in foreign countries. You need this open-mindedness in principle, otherwise you can’t deal with the insecurities a job like this entails.

Tracing your grandfather led you to making a special trip to New York. How has your research changed your view of the city?

In general, my view of the city stayed the same. The conscious walks in his footsteps made the difference on that trip. I went up to 196th Street, walked along the Hudson, and I knew: He was here, too, this is where he took photos. That was quite touching, and it made me think about what it must have been like 90 years ago. But I can separate this image from regular New York, because I know it’s family history. The other New York is just busy, and since I know a lot of musicians there, I was always with other people for the rest of my visits. That certainly provides a different view of the city than the one from a hotel room.

Where there any surprises when you made the research trip for the book?

No, not really. I went back to New York for a week last year, and my schedule was tightly packed, because I knew exactly where I wanted to go, what was important to me in order to get an understanding of how this book was going to work for me. When you begin a book project like this one, you start with a lot of material wondering how to organize it. My first thought was to show a chronological development in his letters: Does he change or not? But that turned out quite difficult, because there was a lot of repetition in his letters. That’s why I structured the book differently. Of course to me, his personal story is important, but for others it’s interesting to learn: What was 1928 like, how did people live? And the chapter about aviation, when the first airplane came to New York from Germany, and the first zeppelin, that’s also a great piece of history. I’m sure my grandfather felt proud it wasn’t a French airship or a Dutch pilot. Back in those days, people felt more defined by nationality, they felt German, for instance. Today, the world has become more international. Especially for young people, it doesn’t matter anymore if someone is from Holland, Italy, Belgium, or elsewhere. At least that sentiment dissolves in those parts of society that aren’t on the far-right.

Now we have swooned about your love of foreign countries and your journeys, and yet the book’s mood is affected by your grandfather’s deep homesickness. Can you even relate to that?

In a way, I can, because I have travelled all by myself, too. And when you find yourself in a foreign culture which feels very distant to you and where you don’t speak the language and it is hard to find someone who speaks yours, that’s when I realized that having a home can be an anchor. And it’s good to be anchored this way and not be lost in the world. That’s what it was like for my grandfather, and his anchorage was Leipzig.

“New York: Past & Present” by Uli Balß was published in German and English in the fall of 2018.

Comments are off this post