When I asked for an interview with the woman who runs a famous Upper West Side flea market, the reply hit me with two surprises. A man, not a woman, answered. And he did so in German.

Turns out Marc Seago took over the flea market from Juli Ra and has been in charge since shortly after it was renamed Grand Bazaar NYC in 2016 (it had been called Green Flea for 40 years). Marc’s vision for the market is indeed grand, he wants it to become THE market of New York City, turning the neighborhood schoolyard into something that represents the whole city on Sundays. And when you talk to him about it – you can easily meet him every Sunday on that school yard or inside, listening to one of the vendors placed in the school’s cafeteria – he most likely won’t stop gushing about diversity. On the market. In New York. And elsewhere. And he should know.

Marc Seago

was born in New Orleans and grew up in Korea, Taiwan, Germany, and in between also Australia and the Dominican Republic,

works as a marketing consultant and runs Grand Bazaar NYC,

moved to New York in 1997,

lives in Kips Bay (Manhattan),

and places his meetings on a rooftop rather than in an office.

While Marc’s parents moved from continent to continent, the American-born grew up in Korea, Taiwan, Australia, and Germany. Luckily for me – and frankly, for you, too – he agreed to share how growing up in many different cultures has affected his life and his view on this country. And although he grasps every opportunity to practise his German, which is really good, we did this interview in English.

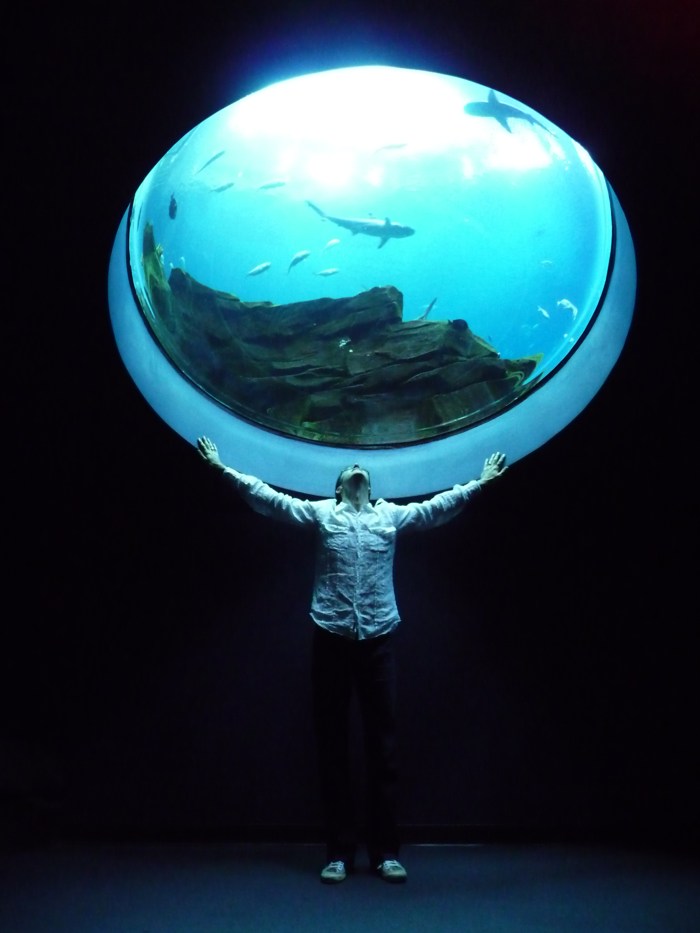

And then there was another surprise waiting there for me: after I learned all this personal stuff about him, I asked Marc to quickly pose for a photo – and he winced. He wouldn’t do it. I briefly wondered how he managed to travel around at least 60 countries without having his picture taken all the time. He showed me what his social media profile photo looks like, and I laughed.

He allowed me to use it in this article – and he even sent me a second one, which you will find further below. Along the way, you’ll learn why the second most common small talk question will make him walk on eggshells, what it means to run a flea market, what a third culture kid is, and how both of us struggled with our hairstyles (well, to be more precise, other people did).

So there is this term, “third culture kid”. How would you explain that, Marc?

Marc Seago: A third culture kid or TCK is someone who grew up outside their parents’ birth country. Those parents are very often business or government expats, they are in the military, or, less than in former times, missionaries. Some, like the military, are more sheltered than others. It also depends on which country they are in. Obviously, an expat in Kuwait will have a more restricted exposure to the country and culture than someone who lives in Hamburg. In Germany, you can freely go everywhere: Even as a kid who is ten or eleven years old, you are sent to school by yourself, you don’t need a bus or a chauffeur driving you everywhere. So the kind of experience third culture kids have really depends on the country, the city, the purpose and the length of the stay. And, at least based on my own experience, it depends on the parents. My parents were very open, we often travelled and really went off the beaten path. Others choose the standard multi-national hotels, they stay in certain gated communities. All that leaves different impressions.

For you, those impressions come from Taiwan, Korea, Australia, and Germany. How long did you live in Hamburg?

With coming and going, it’s 14 years if I remember correctly.

And part of it was you still being in school?

Yes, I went to international school in Hamburg.

Are your parents American?

My father was American, my mother was actually German, she was from Sylt, and they met in Nigeria, in Lagos. They moved all the time because my dad worked in oil, and my mother worked in hospitality.

Growing up in different places, where do you feel you belong – or do you feel that at all?

That is an interesting subject. A lot of people have difficulties understanding that someone doesn’t feel very nationalistic. The way I grew up, travelling everywhere, having cross-cultural parents, growing up as a third culture kid, always surrounded by international people, I never really had an identity like: Oh, I’m American. For a while, I found that troubling, because everybody had to identify as something. You had to fit in. But very often I couldn’t relate, they were talking about something I didn’t understand, because I wasn’t in the U.S. for so many years.

How did that change when you moved to the U.S.?

We briefly moved back once early on after we’d been abroad. I remember as a young child, two or three weeks, maybe a month after we had gone back to New Orleans, I came home from school and I told my mom: “I wanna go back home! Back to Taiwan!” So at the time, Taiwan was my home, because that was where I had grown up until then. So my identity came from the enviroment in which I grew up, the people, the surroundings, and not a birth place, a passport or anything like that. What I love about New York today is that I am basically a subway ride away from Chinatown, from Koreatown, from Little Italy, you name it. That diversity is reflective of how I grew up, and I think that is one of the reasons of why I liked New York. And I think it is pretty representative for a third culture kid to gravitate to metropolitan areas like New York or London, particularly if they grew up exposed to very different environments and cultures.

If I get that right, some third culture kids take something from each of the two or three cultures they are exposed to and then form their own. Can you describe what your cultural identity looks like?

Definitely German/European, and then American, and the rest is a mix, it’s all global, it’s a hybrid. I feel just as comfortable in a room full of Asians as in a room full of Africans. I look at the world as a playground, as a fun place. I get asked where I’m from all the time. Some people can’t place me, because I have a very mixed accent.

That’s true! Right now, you sound a little bit Dutch.

I get everything! I get Dutch, Irish, South African, Australian. One person even said: “You sound like you come from Hong Kong.” I disagreed with that one (laughs).

How do you feel when people ask you where you are from?

As a third culture kid it is tough to answer that. You have to always consider who is asking and why they are asking. There are some people who just want to know because, let’s say it that way: They want to have a negative thing going on.

You mean like: Go back where you came from?

Not only that. If you say: “I’m American” when an American is asking, they will still find something negative to say if that’s what they were after. Basically, they won’t believe you. And if it is just a curious question, and you say: “I’m American, but I grew up there and there”, then they will insist: “Okay, but where are you from?” If you don’t commit to that box, they are offended or confused. So sometimes it is tricky to decide how honest you want to answer that question. You can say: “I’m American, I have a weird accent because I’ve lived here in New York.” Or you can say: “Yeah, I lived in a couple of countries, I am more multi-national, I don’t have a national identity” or something like that. You can offend people with either answer. But at the end of the day, I say: We all share the same planet, so what’s the difference?

Ha, there you go. Do you ever answer by saying “I’m from Planet Earth”?

There are a lot of people who will be offended by that. Particularly the more nationalistic they are. For them, you have to fit in that box.

What did you like about Hamburg when you lived there?

Oh, I have to say: When the weather is really nice in Hamburg, it is probably one of the most beautiful cities! Everybody smiles, everybody is moving slowly, it is so green, it has so many rivers and lakes. I also liked that the city is quite diverse, it has everything from the old Hanseatic traditional side, you have the port, you have have the nightlife, the bars, the seedy part, and then you have Blankenese and Pöseldorf, the equivalent to the Upper East Side here in New York. And even Reeperbahn, the seedy part, is super clean in comparison to New York. Hamburg has a lot of creative agencies, models and designers, and on the other hand, you have traditional businesses there, and very conservative people. And in general, people are very straight-forward, very friendly. When Americans say friendly, they mean “Hey, how are you doing” and all that stuff, but in Germany, at least in Hamburg, it is more like this: If you have a question, you usually will get an answer, and it will be straight-forward. Those are aspects I really appreciate in Germany and in Hamburg.

On your professional website, you openly advertise that you can both work New York style and German style. How do clients respond to that?

I think I am quite good at thinking ahead as many steps as possible. That is where I think I apply the German style. However, that can be challenging, because sometimes you have a client or a boss who doesn’t have that vision. Some people just want to go from A to B, B to C, and they don’t think what comes after B until they got B done and then figure it out from that point. So you say: When we do this to get to B, that will become a problem when we go to C – and they don’t care.

Both approaches have their pros and cons: You can plan and plan and plan and meanwhile the chance of executing your plan might pass, and on the other hand, when you quickly do things before you really plan, you also test things. I think that makes Americans less afraid of making mistakes.

Yes, that is a very important aspect. If you go bankrupt in America, the question they ask you is: What did you learn? So they very often think there is a great chance you won’t repeat that mistake. Whereas in Germany, it is very hard for someone who goes bankrupt to get back into business. They could have probably learned a most valuable lesson from it, and moved on to do great things, but they are burdened down by a mistake they did in the past, carrying it for the rest of their lives. In the U.S., viewing a mistake often means that as long as you make clear that it was a mistake and express what you learned out of it, you can move on very quickly. Even though you get fired very fast for making a mistake.

Wait, what?

That is a stupid accountability idea: The one who made the mistake gets fired. Then they move on elsewhere. And instead of asking within the company: What have you learned?, they are bringing in someone new, who most likely hasn’t made that mistake, and then, who knows, there is a possibility that that mistake might happen again.

Is there anything you learned in your time in Hamburg that you think you couldn’t have learnt anywhere else?

That is hard to say. Because I grew up going to international schools, I always had international people around me. I didn’t grow up like a typical German in Hamburg. But I did competitive sports, track and field, and high jump was my strongest discipline. What I learned in Hamburg that I think I probably wouldn’t have learned as well elsewhere is a certain amount of discipline to do things. In Germany, when someone says “I’ll do it”, they more or less do it. In comparison, over here, when someone says he’ll do it, you have to follow up, you have to keep track of it, and that is a huge amount of waste of time. That was one of the big changes in my professional life, and something that I do miss and appreciate and I learned to respect about Germany.

Nowadays, your work includes running a flea market. How did you get involved with Grand Bazaar NYC?

I was a marketing consultant, and once or twice a year I do pro bono work. I saw a posting that asked for a marketing plan for a flea market, and I was like: “Oh! That’s 20, 40 hours of work, that should be easy.” Then they asked to implement those ideas, and we renamed it from Green Flea to Grand Bazaar NYC. That was in September of 2016, and shortly thereafter, they asked me to take over the market and run it.

What does that entail?

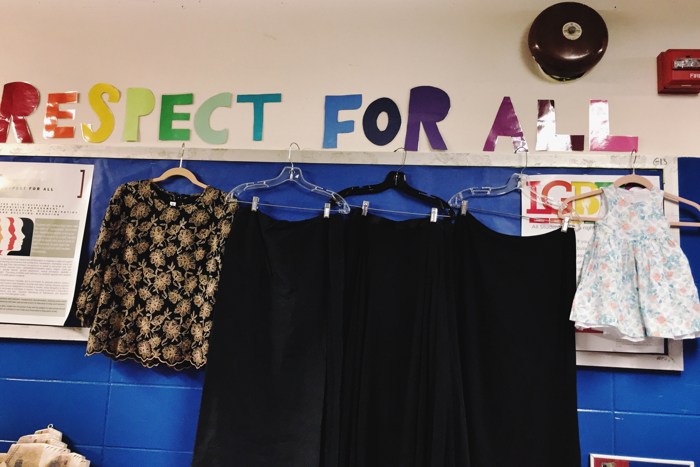

In our tagline we say “artisans, antiques and edibles”, so we curate a mix of these three and position the corresponding vendors on our space, every week anew. On top of that, the proceeds of the Grand Bazaar – which come from the vendors’ fees and donations – go to four public schools, benefitting about 4000 students.

This charitable aspect has been part of Green Flea for a very long time. Where exactly is the money going?

There was always a market in this location for 30-something years which was started by school kids’ parents. Today, the market gives the money to the parent associations of each of these four schools. And they use it for whatever they need for their budget, from buying books or ACs to organizing a chess tournament to class trips.

What kind of vendors do you pick for the market?

We have artisans who make everything from furniture to jewelry to lamps to clothing. Some of them are hand-made in New York, others are international. For example, the Turkish towels that we sometimes have are made by a family-owned business that employs almost a whole village. New York is a diverse city, so we have Persian and Afghan rugs, Tunesian pillows, African masks, Chinese sculptures. Our second category, antiques, also contains vintage and collectibles. For example, there is Larry, also called the King of Flea, who brings something different every week. We also have a vendor who fixes up vintage toasters so they work. And we have someone who is a cross between vintage and artisan: He finds antique radios and not only fixes them up, but also makes them blutooth-enabled. That’s how we curate: We want to feature things that you can’t find anywhere else. The third kind of vendors sells food, and their section comes in two parts: The food that you can consume right away, and the one that you can take home. For example, we have award-winning pupusas from El Salvador, Italian arancini balls, twisted potatoes, and so on. Then we have maple syrup, various hot sauce vendors, or occasionally we have small-batch, family-owned olive oil.

We have artisans who make everything from furniture to jewelry to lamps to clothing. Some of them are hand-made in New York, others are international. For example, the Turkish towels that we sometimes have are made by a family-owned business that employs almost a whole village. New York is a diverse city, so we have Persian and Afghan rugs, Tunesian pillows, African masks, Chinese sculptures. Our second category, antiques, also contains vintage and collectibles. For example, there is Larry, also called the King of Flea, who brings something different every week. We also have a vendor who fixes up vintage toasters so they work. And we have someone who is a cross between vintage and artisan: He finds antique radios and not only fixes them up, but also makes them blutooth-enabled. That’s how we curate: We want to feature things that you can’t find anywhere else. The third kind of vendors sells food, and their section comes in two parts: The food that you can consume right away, and the one that you can take home. For example, we have award-winning pupusas from El Salvador, Italian arancini balls, twisted potatoes, and so on. Then we have maple syrup, various hot sauce vendors, or occasionally we have small-batch, family-owned olive oil.

And pickles!

Yes, every major, important market always has pickles and olives (laughs). And occasionally we have food truck join them.

How come?

We run themed events parallel to our existing market. For instance, we have a food truck festival with 12 to 15 gourmet food trucks which come in in addition to regular vendors. Or we have between 15 and 20 ice cream vendors for one special day. We also do a kid’s bazaar with around 25 kid-centric vendors in addition to our 140 regular vendors. For these events, we give those vendors a dedicated section for that day. We are currently the largest market in New York, and also the most diverse. Everyone else is focused on either niches or certain categories. They are an independent artists pop-up that only happens every few weeks, or they are a flea market and they don’t really have many artisans or food.

But what about Brooklyn Flea or …

Brooklyn Flea used to be a lot larger, they have gotten smaller. They have two locations, and their maximum size right now is roughly 80 vendors. We average about 140 vendors throughout the year.

Still, their focus seems similar.

They have food, they have some of the artisans, yes. But they don’t have as much diversity. If you go elsewhere, you find more or less the same vendors every weekend. At Grand Bazaar, however, we rotate our vendors. This year, we will probably have more than 800 vendors go through the market. Some are permanent, and some come only for one particular themed event. Some would love to be there every Sunday, but we only accept them two, three times a year.

I’ve been thinking about how to politely ask about an observation I made: Many antiques sellers seem to be a little older …

I think that is fairly typical. On the vintage side, there are some younger, hip, trendy individuals. They want to be original, less mainstream, and they are really into vintage fashion. And we have the young entrepreneurs who make baked goods, soap, or jewelry and are very creative in developing products and designs. And on the far, far other end, we have who is probably the world’s oldest vendor, her name is Mathilde Freund.

Oh, she is still there? She’s gotta be 101, going on 102 in August!

That’s correct! So you really meet generations at the market. Some are super friendly, others are a little grumpy, some are very knowledgeable and they want to share their wisdom, while others just want to grow a business and enjoy life and are all over social media.

Why do some vendors stay away from web shops or social media?

They say maintaining a website would be too much work, they’d rather come to the market and occasionally sell to wholesale, if a store wants to buy something. I would say particularly on the vintage, antiques and collectibles side, 80 percent of our vendors, if not more, don’t have a digital presence. Many artisans don’t have a website either, for two reasons: Either they make one-of-a-kind items, or they are afraid that their designs are stolen. And some are. And because anybody can go to the market and buy their designs, some of the vendors won’t sell if they have a suspicion that it’s someone who wants to mass produce their stuff. It is a very interesting job hearing the different stories and concerns of these vendors. Some of them want to have as much publicity as possible, and others just want to sell, they don’t want the publicity.

Sounds like even the challenges are diverse. What did you have to adapt to when you moved to New York?

Good question, that was a long time ago. Back then, New York was still shady in certain areas, and just because I had long hair, everybody thought I was a junkie. So one thing I hated over here, and I think that applies to a lot of places, are the stereotypes. It was challenging to get jobs at times. They would say: “This is off the record: We would love to hire you, but you have to cut your hair.” And I never experienced that in Germany, though the country has its own downsides. Anyway: When I travelled the U.S. with long hair, the police would pull me over.

But those times are over.

Well, I don’t have long hair anymore.

Plus, maybe the police’s policy changed?

Well, it changed the moment I cut my hair. As soon as I had short hair, I wasn’t asked to show my ID, I wasn’t asked to step over, all that stuff disappeared.

That is not unique to the U.S. Having dreadlocks in Germany, I shared that drug dealer suspicion with you over there.

Oh, that would happen here, too, depending on where you are.

No, it never did happen to me here. And I think that’s because I am white. That it’s due to privilege.

That’s true. Funny thing about New York: I quickly learnt that if there is any situation with the cops, throw in a foreign accent, and they think you are a tourist, and they are nice. When they think you are not a tourist, they are not as nice. I’ve seen that very often.

That’s interesting. And also a choice that you and I can make, but many Americans can’t.

A friend of mine and I used to live close to each other, and when he wanted to use a cab, I usually hailed it, because they wouldn’t stop for him. He’s black. I even saw black people further down the street who had raised their hand, and the cab would drive right past them to me. Then I would just hold the door and wave them over.

Those are the little things you don’t even notice, let alone try to change, when you aren’t aware of your privilege.

It is astonishing that so many people here in the U.S. and even politicians say that it is not that bad. What are they talking about? That is something I did notice when I came from Germany to here: how racist a lot of people are and how racist the culture is. And as soon as you leave New York, it becomes more tangible. As a kid in New Orleans, I was teased, too, just because my mother was German. I got to hear lots of ugly things.

The other N-word?

Yes, exactly. I didn’t want to say that. But I got to hear it quite often. It is an ugly truth that this is not going to go away by denial. It is not.

Did you ever feel out of place anywhere?

Because I was always surrounded by people who looked a little different, there was a time when I felt a little bit out of place when I was in a room where everybody looked like me. As soon as there was more diversity, I felt more comfortable and relaxed. For me, the color of the skin or the nationality never played a role. Who is that person? Is that a nice person or not, interesting or boring? That’s really what it comes down to.

Grand Bazaar NYC is every Sunday, year round, at a school yard and cafeteria at 100 West 77th St (at Columbus Avenue) from 10 am to 5:30 pm. Find out more on their website.

Comments are off this post